The hidden trade-off of growing corals quickly

Faster Growth Isn’t the Same as Healthy Reefs: What Mineral Accretion Technology Really Does to Corals

Research from Indonesia reveals important trade-offs in a popular coral restoration technique.

Electro-mineral accretion (EMA)—often known as biorock—is widely promoted as a way to speed up coral growth on degraded reefs. By running a low-voltage electrical current through submerged metal structures, minerals precipitate onto the frame, providing a hard substrate and boosting coral skeletal extension. The visual results can be impressive.

But does faster growth actually mean healthier, self-sustaining reefs?

A new peer-reviewed study led by Andrew C. F. Taylor and conducted at a coral restoration site in Lombok, Indonesia, suggests the answer is no—at least not by growth metrics alone:

What the study examined

Rather than focusing only on how fast corals grow, the study measured multiple biological traits that determine whether restored corals can survive, reproduce, and contribute to long-term reef recovery. Researchers compared corals grown on EMA structures with nearby naturally growing colonies, examining:

Skeletal growth rates

Reproductive output (fecundity)

Polyp density

Skeletal density (a proxy for structural strength)

Two common reef-building species were used: Stylophora pistillata and Acropora muricata.

The key findings

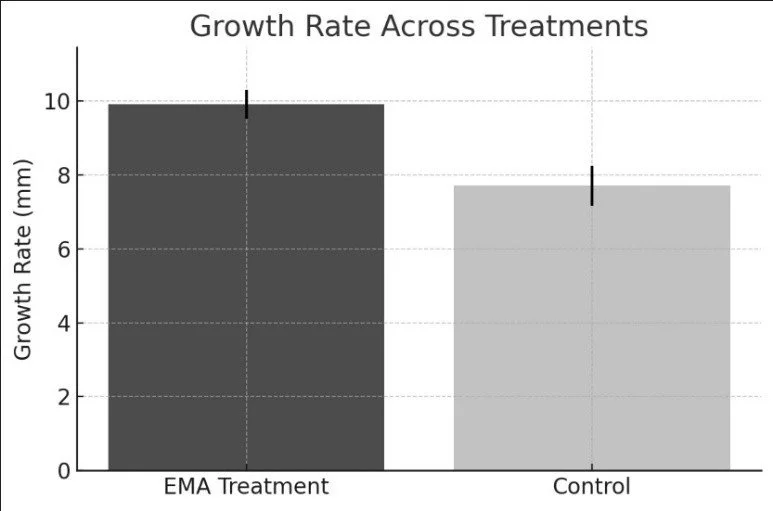

1. EMA corals grew faster—but at a cost

Corals on EMA structures showed significantly higher skeletal growth rates than natural colonies. Over a five-week period, Acropora muricata on EMA grew about 29% faster.

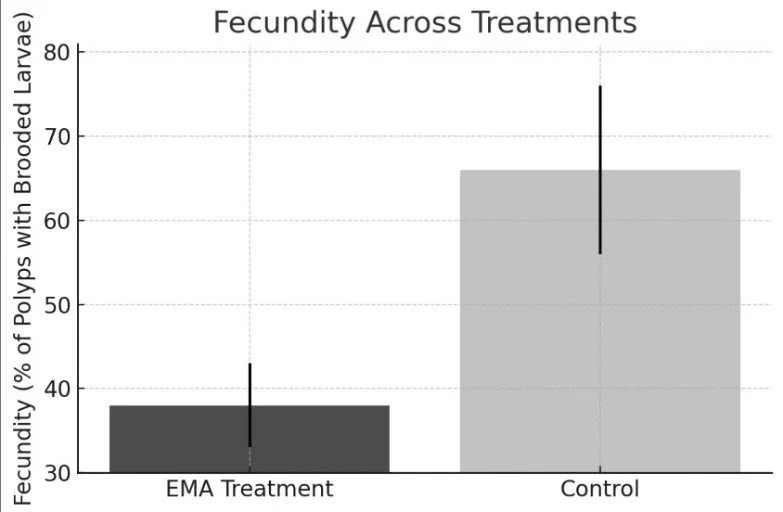

2. Reproductive output dropped sharply

Despite faster growth, EMA-treated Stylophora pistillata colonies had ~40% lower fecundity than natural corals. Fewer polyps contained brooded larvae, meaning less potential for future recruitment.

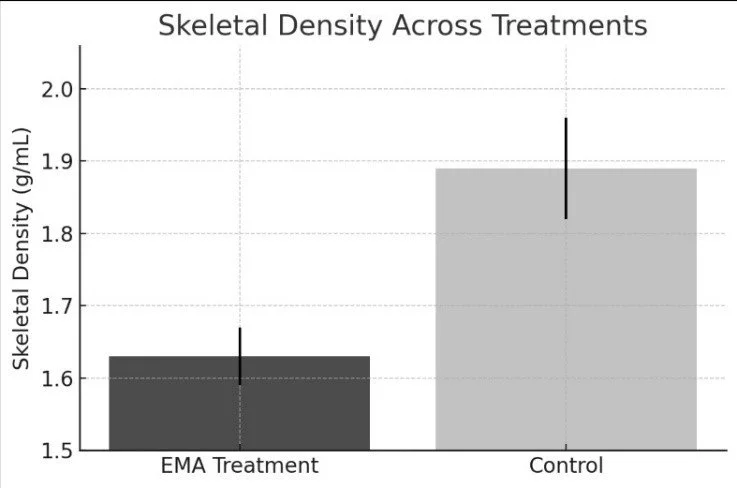

3. Skeletons were lighter and less dense

EMA corals produced skeletons that were significantly less dense than those of naturally growing colonies. Lower skeletal density can translate to weaker structures that are more vulnerable to breakage, storms, and bioerosion.

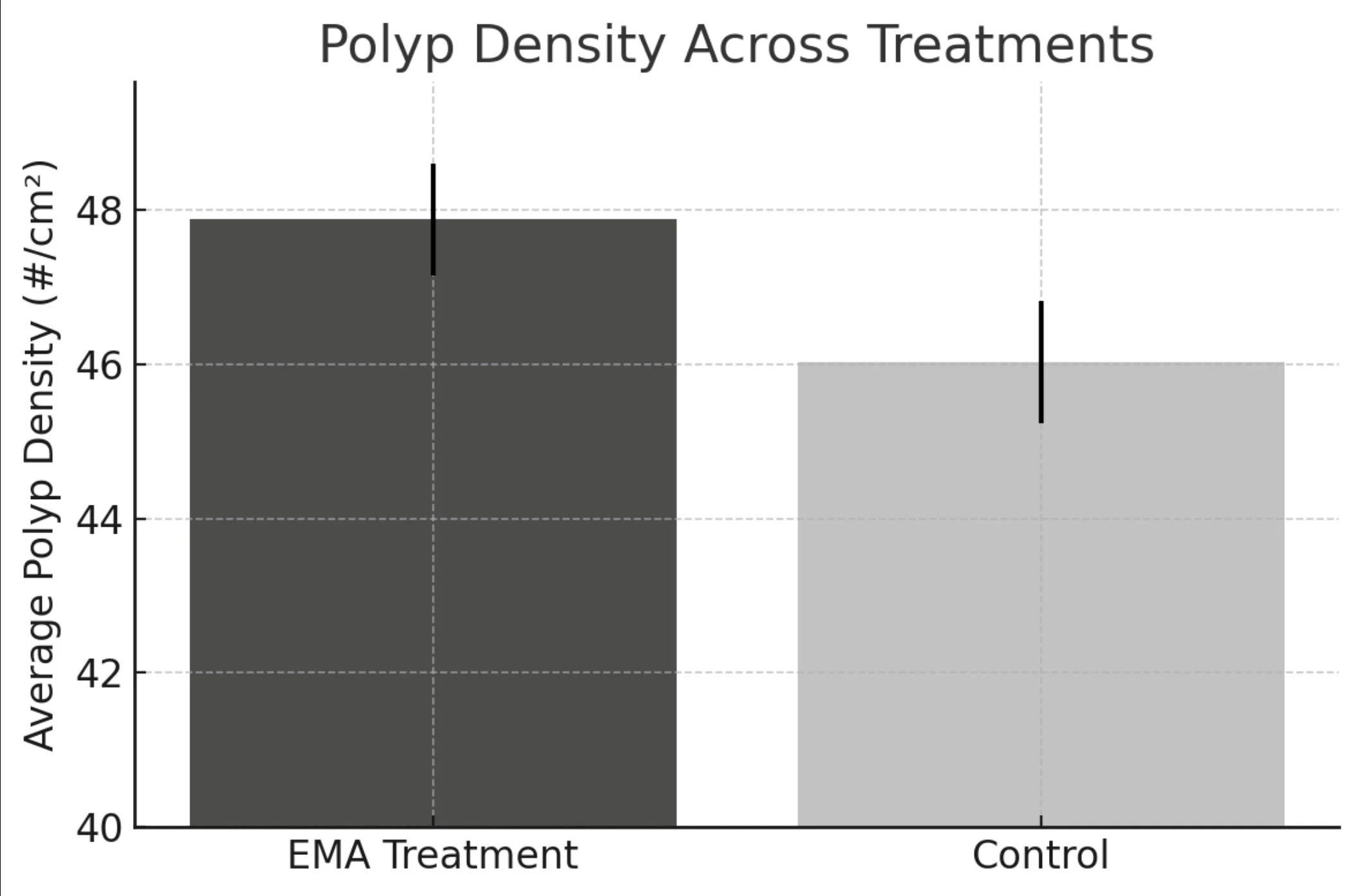

4. Not all traits changed

Polyp density remained similar between EMA and natural corals, indicating that some aspects of coral structure were unaffected.

Why these trade-offs matter

Corals operate under a finite energy budget. Energy invested in rapid skeletal extension is energy not available for reproduction or skeletal strengthening. This study provides real-world evidence of a classic ecological trade-off: enhanced short-term growth versus long-term fitness.

From a restoration perspective, this is critical. Reefs don’t recover just because corals grow quickly. They recover when corals:

Reproduce successfully

Contribute larvae to surrounding reefs

Build strong, resilient reef frameworks

Fast-growing corals that reproduce less and form weaker skeletons may increase short-term coral cover while quietly undermining long-term reef persistence.

Implications for coral restoration

This research challenges a widespread assumption in restoration practice: that accelerated growth is a reliable indicator of success. The findings suggest that EMA may be useful as a short-term stabilization tool, for example to consolidate rubble or establish initial structure—but relying on it as a long-term solution risks creating reefs that look healthy without functioning like natural systems.

The study argues for a shift toward trait-based restoration monitoring, where growth is evaluated alongside reproduction, skeletal integrity, and resilience. Without these measures, restoration projects risk optimizing for appearance rather than ecological function.

The takeaway

Electro-mineral accretion can make corals grow faster—but faster growth alone does not equal restoration success. If coral reefs are to persist in a changing climate, restoration methods must support reproduction, structural strength, and long-term resilience, not just rapid skeletal extension.

Effective restoration isn’t about how quickly corals grow.

It’s about whether they can survive, reproduce, and rebuild reefs that last.